Jack McKeown

My earliest memories of visiting relations were of occasional trips in the fifties to what was always known as Grannies in Sheetrim. Indeed I as a child looked to the comfortable figure of granny to protect me from the more formidable personage in the rocking chair in the corner, sucking on his pipe. My sisters Patricia and Bernadette remember this differently. Patricia was Jack's favourite and he used to protect her against granny's scolding tongue! Bernadette used to holiday in Sheetrim, where she established a close and lasting friendship with Jamesy's son, John McKeown.

Jack McKeown in his latter years was a gruff but friendly man, much given to taking a hand out of his grandchildren. To me he was a figure of great skill, power and strength for I was terrified of the huge horses in his forge which grandfather shod and treated as if they were his pets. Occasionally he would let me help and I would swing my weight on the huge bellows to blow a sharp blast of air into the coke fire. Within seconds the grey steel would turn red hot and glow fiercely. In his left hand Granddad would lift the metal with a pair of grips, then hammer and shape it on the horn of the anvil with strong and accurate blows from the hammer in his right hand. I had always imagined the horseshoes came ready made and the smith had only to fit them! There was much shifting and turning of the tempered steel to fashion that distinctive shape. How would he get the holes in them to take the nails? A punch appeared in his left hand and with a few well-directed sharp blows, the seven holes appeared in the shoe. Was it ready to fit? Not yet. I was ordered to raise the fire and I applied my weight to the bellows. The shoe was plunged into the hottest corner. When it was extracted again, glowing red, Jack went to the horse that was waiting patiently all this time, occasionally snorting and all the time filling the forge with its distinctive odour. A sharp tug on its lower leg and a barked order and the leg was gripped firmly between Jack's knees. Suddenly the red-hot steel was applied to the horse's foot and a singeing sound and a strong burning smell filled the forge. I stepped back instinctively, expecting the horse to rear up in pain and fright. Nothing happened. Jack examined the scorch mark and the shoe.

THE FORGE by Seamus Heaney

All I know is a door into the dark. Outside, old axles and iron hoops rusting: Inside, the hammered anvil's short-pitched ring, The unpredictable fantail of sparks Or hiss when a new shoe toughens in water. The anvil must be somewhere in the centre, Horned as a unicorn, at one end square, Set there immoveable: an altar Where he expends himself in shape and music. Sometimes, leather-aproned, hairs in his nose, He leans out on the jamb, recalls a clatter Of hoofs where traffic is flashing in rows; Then grunts and goes in, with a slam and flick To beat real iron out, to work the bellows.

A small correction was necessary. He returned to the anvil and delivered a few more blows. Content at last he came back to the horse and repeated the earlier order. The leg was bent and delivered obediently to his crouched figure. Surely the animal would protest at the nails being driven fiercely into his foot? No. Sometimes the point of the nail would penetrate the horn of the horse's foot and then Jack would have to nip off the pointed steel with another tool. Further hammer blows were necessary to complete the job. Now one shoe had been fitted. There were three more to go. The heat in there was intense and the smell of horse and of man's sweat oppressive, yet I felt I could have stayed forever. This was real education. I was paid a penny for my efforts. When Mum and I returned home that evening we were carrying a basket of eggs and some “country butter”. This was the homemade salted kind that I had earlier helped to churn in the kitchen. I didn't mind the work but I (and all my siblings) strongly objected to having to eat the foul-tasting stuff, but we were made to. Waste not, want not, we learned. And in those days you did what your parents told you to without question.

Rose and Shauna at Sheetrim

I remember my first ever trip to Sheetrim. This was before anyone in the family had a motorcar, or a boyfriend with a car prepared to drive us out “to the country”. In later years, when Mary and Patsy Mooney were courting, we had many trips with them. Patsy became a familiar figure in Sheetrim and a firm favourite with all who lived out there.

I was just eight that first time when Mum and I caught the Crossmaglen bus. My abiding love for the South Armagh countryside dates from that first bus ride. I was enchanted by the view all the way, and by the time we arrived in Cross I felt we had traversed the whole of Ireland. Mum inquired about a connection to Cullyhanna (and from there, I presume, to Sheetrim though later I am told Pete O'Hanlon's taxi in Cullyhanna village would be hired for the last leg) and asked about times of buses returning to Newry. There would be one on Thursday, the man said, and suddenly my joy turned to panic. We would not get home for three whole days! The magic went out of South Armagh at once. Of course he was jesting, as Mum knew, and I had to be reassured. It was still another hour before we arrived at Grannys.

It may seem extraordinary now but I felt that first time that Sheetrim was technologically advanced compared to us. There were gadgets there I didn't recognize or understand and no one bothered to explain them to me. But there was one that I did recognize. It was an early gramophone. At home we had no radio (or TV of course) or any machine to deliver music into the house. But we did have electricity. Sheetrim did not, yet it had a gramophone. I couldn't understand this. My Mum eventually explained and demonstrated how the record-player (complete with cornet-shaped loudspeaker) worked. It had to be manually cranked and the sound was delivered by the friction of the needle against the spinning disc. They were 78's of course and all of the John McCormick style (“Oh to be in Doonarie” etc) that I loved. Bill Hailey and the Comets would not introduce the world to rock and roll for another year yet! I looked forward to every subsequent trip to grannys just to hear that gramophone. Eventually it was there no more. Only recently I discovered from Rosie that granny was offered a price she couldn't refuse for it from a wealthy American couple.

The farmhouse had a maze of outhouses adjoined to it, and it seemed one at least always contained a newborn calf. Even they towered over me and left me apprehensive. The chickens in the shed next to the farm gate were my favourite. They offered no threat! In addition I was sometimes charged with the task of collecting from the coop any eggs that had been laid. In the shed behind this one, looking out over the crossroads below, Granddad would milk the cows. He loved to call me in from outside so that he could redirect the jet of milk from the cow's teats into my face. This amused me surely, but not nearly so much as it amused him! Later this became Jamesy's favourite joke too.

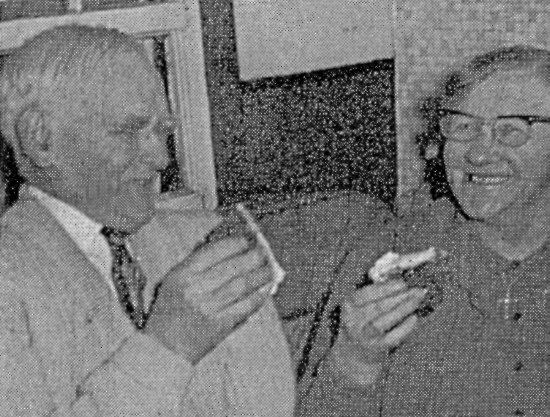

Jack and Mary's Wedding Anniversary

It's hard to believe that the farmhouse had no running water (another chore was to fetch a pail of water from the pump - hand-cranked also - at the gate) and was lighted by gas-lamps suspended from the ceiling. (Indeed though they seemed to me to belong to a bygone age, they were then a recent addition to the house. My sisters remember the paraffin lamps that preceded them. Rose still has one of these upstairs today!). I used to love to watch the gas lamps being lighted in the early evening, and smell the pleasant odour of the burning gas. It was long after my grandparents' deaths that Jamesy and Rose finally had a bathroom fitted to the house. I remember the pleasure of first using the indoor, flush toilet. On previous visits we had had to do what all the generations before (including of course, my mother and her siblings) had done: that is, sit on the plank in the dry toilet outside, and attempt to hold our breath for the duration! But I'm getting carried away! I must return to my family history.

Jack McKeown was born on 26.1.1889, the third child and third boy born to the union of James McKeown and Mary Boyle. Though Mary was from Broomfield, Monaghan her mother was a Fee from Culloville.

Jack's elder brothers were James and Patrick (Paddy). Mary and James had twins, Bridget and Michael, who both died in infancy (when they were 14-15 months old). Their next (and only) surviving girl child was named after her mother. In adult life this girl married Hughie Kelly. They went on to have two children Mary Maguire (Kelly) and Thomas. That story has been told. The last born to Mary and James McKeown was again christened Michael.

The McKeowns grew up on a farm in the townland of Lissavery, near Crossmaglen. The farm was small and poor and was never going to provide a future for any of the children. When he left his teenage years Jack McKeown was determined to seek his fortune in America. There was the complication that by then he was walking out with the daughter of a neighbouring farmer Owen Sheridan. Owen, originally of Tullyard had married Bridget McArdle from the Mounthill area, close to the Louth/Armagh border. (Bridget had been born in Louth on 12 October 1859 of Patrick Thomas McArdle and Bridget Hanlon - witnesses were Owen Woods and Elizabeth McKeown of Castletown). Mary Ann (born 1889) (later to be my grandmother) was the youngest of his three children. The eldest, Michael, became the father of Gene (see previous story). Cissy (proper name Bridget) would later marry Jack's older brother Patrick. Mary was Jack's sweetheart. Jack asked her to come to America with him but she refused. She was unwilling to settle in such a pagan country. Eventually Jack decided to go without her. The lad walked from his home to Crossmaglen where he hired horse-drawn transport for the journey to the port of Greenore in County Louth. His mother climbed a hill beside their home to catch a last glimpse of her departing son whom she feared she might not see again. Jack worked his passage on a coal boat to Liverpool on the first leg of the journey. In England he worked for some months in a steelworks in Barrow-On-Furness.

Jack McKeown again worked his passage from Liverpool to New York on the ship CAMPANIA, arriving on or about 23.4.1910. Jack seemingly did not intend to settle in the USA when he first left, for he had paid an initial payment on a house and farm at Sheetrim. This is where he intended to live when he had married Mary. He was going to America to pay for it. Before he left, Jack had learned his father's trade and was a qualified blacksmith. However in the New World he worked amongst other things as a labourer on a farm. Apparently he found he liked America and hoping to persuade his sweetheart at home to join him there, he applied for American citizenship as soon as he was permitted to. On 25.5.1912 he received authority to proceed with his application. Then two years later (probably anxious not to lose Mary) he decided to return to Ireland. His brothers - by then also resident in the USA - stayed, married and settled in America.

Jack McKeown

Jack had been in the States for four years. He hadn't made his fortune but he had saved enough to pay for the land. While he was away, Mary had been walking out with another man, convinced Jack was gone forever. She went back to her old boyfriend. The other man never subsequently married.

Jack McKeown again wanted Mary to go to America and settle there with him. She was still determined not to. He accepted this and they married in February 1915. On the wedding night they returned to the home he had bought at Sheetrim in 1910. They had to burn a candle for light, as they had no paraffin lamp. One was bought the next day. Jack immediately began to build the house and the farm.

To begin with there was just a bedroom, a kitchen and a barn. The roof was high pitched so that a low but narrow upper level could be added. This is referred to as a one and a half storey farmhouse and today it is the only one of its kind still occupied. Jack had to earn his living so the first priority was to add a forge. As his family grew, more living accommodation was needed. The children born to Jack and Mary, with their dates of birth, were as follows :

| 12 May 1916 | James |

| 14 September 1918 | Peter |

| 12 February 1920 | Delia |

| 2 October 1921 | Mary Ellen |

| 17 December 1924 | Kathleen |

| 24 April 1927 | Rita |

Though in the parish of Cullyhanna, the children were sent to school in Annamar (in the parish of Crossmaglen). This was because Jack had a strong disagreement with Master Devlin of Cullyhanna School over the Sinn Fein election of 1918. One of Jamesy's companions was Tom Fee (who however attended Cregganduff School, where his father was school master) later to become Cardinal and Archbishop of all Ireland. Many, many years later the good cleric would collect the invalid Jamesy on his way to Gaelic Football games at Croagh Park. Often the Cardinal would have to earnestly request Jamesy to temper his language as he was embarrassed by the outburst of profanities (aimed at players and referee alike) that was emanating from the Cardinal's box there!

Mother has a photograph of the old school hanging in her kitchen today. (It is reproduced herein.) It must have been a very good school indeed, staffed for decades by a husband and wife team, with classes of very mixed age as well as ability. I remain impressed to this day with my mother's erudition. Though she never attended a secondary school (nor any other than Annamar) she is familiar, for example, with more of the works of Shakespeare that I ever studied. She was also imbued there with a love of poetry. All future generations of McKeowns were sent for schooling to Annamar. There's a new schoolhouse there today.

The loft was accessed by the narrowest and steepest of stairways. Two tiny low-roofed and narrow bedrooms were built. Later the low room, below the kitchen, was added. It served as two bedrooms. Much later (when the family was reared and we were visiting) it was the parlour room that housed the gramophone and granny's enormous indoor plants. Today it is a small bedroom and the new indoor bathroom. The present kitchen, at the entrance, is also a modern addition. Before all these were built, Jack had to add barns, byres, and haylofts and out-houses for his animals. He was hard working and industrious.

Later he would buy the second farm over the hill (The Rocks) that would become the home place of his first son Jamesy. (This is now John McKeown's home). At one time a farm of land at Annamar was also bought but this was later sold. A farm of land at Dungooley outside Forkhill, but across the border in County Louth in the Irish Free State (created in 1921) was bought for smuggling purposes. It was intended for his oldest son Jamesy. In fact Jamesy was sent to live there. He took an immediate dislike to the isolated place. In the local pub he felt ostracised. He stayed just two weeks. When he returned home with this tale he was sent to work in Scotland, on a building site under a foreman named Mr Kirke. The second son Petie was sent to Dungooley. He didn't much like it either at first. After two or three years there he caught a cold that developed into pneumonia and then pleurisy.

He was brought home for a while to convalesce. While at home he became friendly with Margaret Mary (Maisie) Woods from Lough Ross near Crossmaglen. They married in 1950 and the farm at Dungooley was a wedding present from Jack and Mary. He had to stay there because by then he was a vital part of the smuggling operation that was Jack's chief source of income. On 10 January 1952 their first child Mary was born. Two years later they had a son Peader. This was all their children. Today Mary is married to Philip Cusack, lives on a farm in County Meath and has twins, a boy Peter and a girl Mairaid. Peader is married to Kathleen and they have one boy named after Padre Pio. We McCullagh children would get occasional visits over the years to Dungooley to see Petie and Maisie. I enjoyed these a lot and especially when I realised my mother's embarrassment at Petie's rich language. He didn't think he had to restrain it just because there were children about. [Do you know any auld bad words? he asked my son, some years ago. Answered in the negative, he went on, -Then come here till I teach you some!] His father had been the same. Petie wasn't heavily into home improvements but you would certainly be made to feel at home there. I was and remain very fond of him.

Petie and Maisie McKeown

Jack was a farmer, a blacksmith and a smuggler. He used the first two to facilitate his black market operations. A compartment was constructed under the seat of his cart to hide goods being smuggled. He would take a circuitous route to the agricultural market. Entering the Free State he would buy several bottles of whiskey to resell in Newry to local publicans at a much higher price (until recent years, duty on alcoholic drink was much lower south of the border). One of his daughters would accompany him to throw customs men off their suspicions, but still this leg was the most risky as the bottles could be heard clinking under the seated pair. Jack never seemed to learn or perhaps to bother with the simple expedient of muffling them by wrapping each one in a cloth. With the profits from this, and any animals he was selling at Newry Market, he would buy the metal with which he would make horseshoes for the following few weeks.

In spite of this triple source of income Jack and Mary had it hard rearing their large family. There was scarcely a living to be made from the farm and the smithy combined. 'I'll see you at the fair', was the only promise of payment Jack often received from neighbours whose horse he had just shod. The land annuities had to continue to be paid to the Government right up to the year 1974. These fell due twice a year. Rose McKeown (now living alone in the home place) has the stamped rent books. Granny McKeown (Mary Sheridan) remembered when she was just a girl walking with her own mother the whole way to Castleblaney to pay the land rent to the landowners. In latter years Jamesy (my uncle) used to tell me tales of his and his father's smuggling activities about Cullyhanna and the active connivance of a number of RUC personnel who were billeted in the village's barracks. These men would shine a light in a certain room of the barracks, visible from Sheetrim, to indicate whether or not a certain cross-border route would be patrolled that night. There was of course, some quid pro quo!

Another poetic snippet to give a taste of the 'local colour' of these bygone days!

Canton Of Expectation

Once a year we gathered in a field Of dance platforms and tents where children sang Songs they had learned by rote in the old language. An auctioneer who had fought in the Brotherhood Enumerated the humiliations We always took for granted, but not even he Considered this, I think, a call to action. Iron-mouthed loudspeakers shook the air Yet nobody felt blamed. He had confirmed us. When our rebel anthem played the meeting shut We turned for home and the usual harassment By militiamen on overtime at roadblocks.

Granny Mary was a great housekeeper. In those days farms had to be almost completely self-sufficient. Though they were poor, they were never hungry as they grew their own food. They would not have considered the homemade butter foul tasting as we - my siblings and I - in our supposed sophistication, thought it to be! From her mother, my mother learned to cook and to bake the most delicious homemade breads. She taught me this skill. I remember growing up in the Meadow, we would have flour delivered by the sackful for this purpose. My friends then thought this quaint and amusing (perhaps they felt superior because their parents could afford to buy real bread) and wondered how many months a sackful would last. They were amazed to see a new one delivered within the week. When they tasted the bread their arrogance turned to envy.

I wondered at my mother's skill with knitting needles and a needle and thread. She had to be good to clothe her large family. She learned it all from her mother.

From her mother too she learned how to make sheets for the bed, from these same sacks!

Clearances

The cool that came off sheets just off the line Made me think the damp must still be in them But when I took my corners of the linen And pulled against her, first straight down the hem And then diagonally, then flapped and shook The fabric like a sail in a cross-wind, They made a dried-out undulating twack. So we'd stretch and fold and end up hand to hand For a split second as if nothing had happened For nothing had that had not always happened Beforehand, day by day, just touch and go, Coming close again by holding back In moves where I was X and she was O Inscribed in sheets she'd sewn from ripped-out flour sacks.

My aunt Rose (Jamesy's widow) was the one age with Delia. She was from Tullinavall, Cullyhanna. She remembers how well turned-out Delia and her sister Mary Ellen were when they sang with the choir at Cullyhanna chapel. When she asked, she was told they were the daughters of Jack McKeown, the blacksmith. There were many other blacksmiths in the area then, of course. She was later to meet and marry the girls' older brother Jamesy, who would become the next generation blacksmith.

Jack McKeown's children were well equipped to make their own way in life. There was room only for one to inherit the farm and stay at home. This was my favourite uncle, Jamesy.

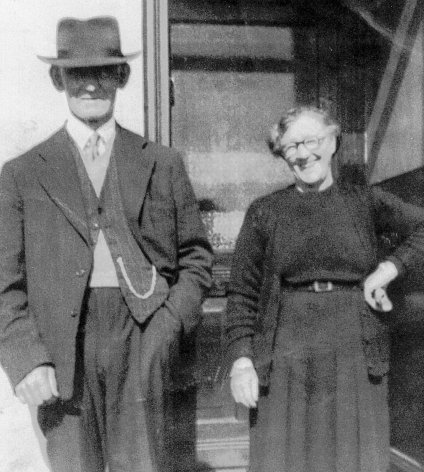

Jack and Mary McKeown around 1940