Ireland In The Nineteenth Century

The Union of Britain and Ireland in 1801 brought no advantage to the Irish people. The British parliament availed of the opportunity to stifle Irish industry and commerce to their own advantage. The short-lived Irish Parliament - totally Protestant and Unionist in its makeup - had in the opinion of Britain failed miserably to protect England from the danger of invasion by the revolutionary French using the disaffected and insurrectionary Irish to undermine England's position. When this home parliament was dissolved, out too went those few laws it had managed to pass to protect Irish trade and commerce. Though nominally equal as part of the greater British Isles the smaller island was ruthlessly exploited and discriminated against. Anti-Catholic laws remained on the statute books for decades and overt and covert discrimination persisted throughout the century. Catholic tenant farmers had little recourse to the law. Rents could be and were raised at the whim of the landlord or his agent. The tenant had no right to fixity of tenure or rent or of compensation for any improvements he made to the land. Indeed where improvements were made the industrious tenant was often evicted on the grounds that the holding was now more valuable than it had been and a new tenant would be prepared to pay a higher rent.

The great majority of the Irish peasantry grew potatoes exclusively - or almost so, with a few other vegetables: a small patch of the better land would be used to raise a corn crop, with which to pay the rent. Potatoes yielded sufficient nutritious bulk to feed the family when the crop was good. Ironically the restricted diet of potatoes and a little milk was sufficient to allow the poor Irish to thrive and multiply for a generation. The country was hugely over-populated when disaster struck. In 1845 there were almost twice as many people living in Ireland as there are today. Unfortunately heads of households had no other asset than the land to bestow on their sons at marriage and it became customary to sub-divide the holding to provide for the next generation. The land was overworked and seldom rested. No crop rotation was possible. No other crop could feed a family for a year. Yields suffered as a result and the crop was ever more vulnerable to disease. Crop failure and hunger was common. Then came the Great Famine when the potato crop failed to a greater or lesser degree for successive years between 1845-1849 bringing with it the greatest loss of life in all Irish history. Other parts of Ireland suffered more because in Ulster there had grown up what was known as Ulster Custom. Under this a little fairness prevailed with some fixture of rent and lease, thereby encouraging land improvements. In areas such as Ardboe there was always, at least for some, an alternative source of food and income from the fish of the Lough. Few perished here from starvation.

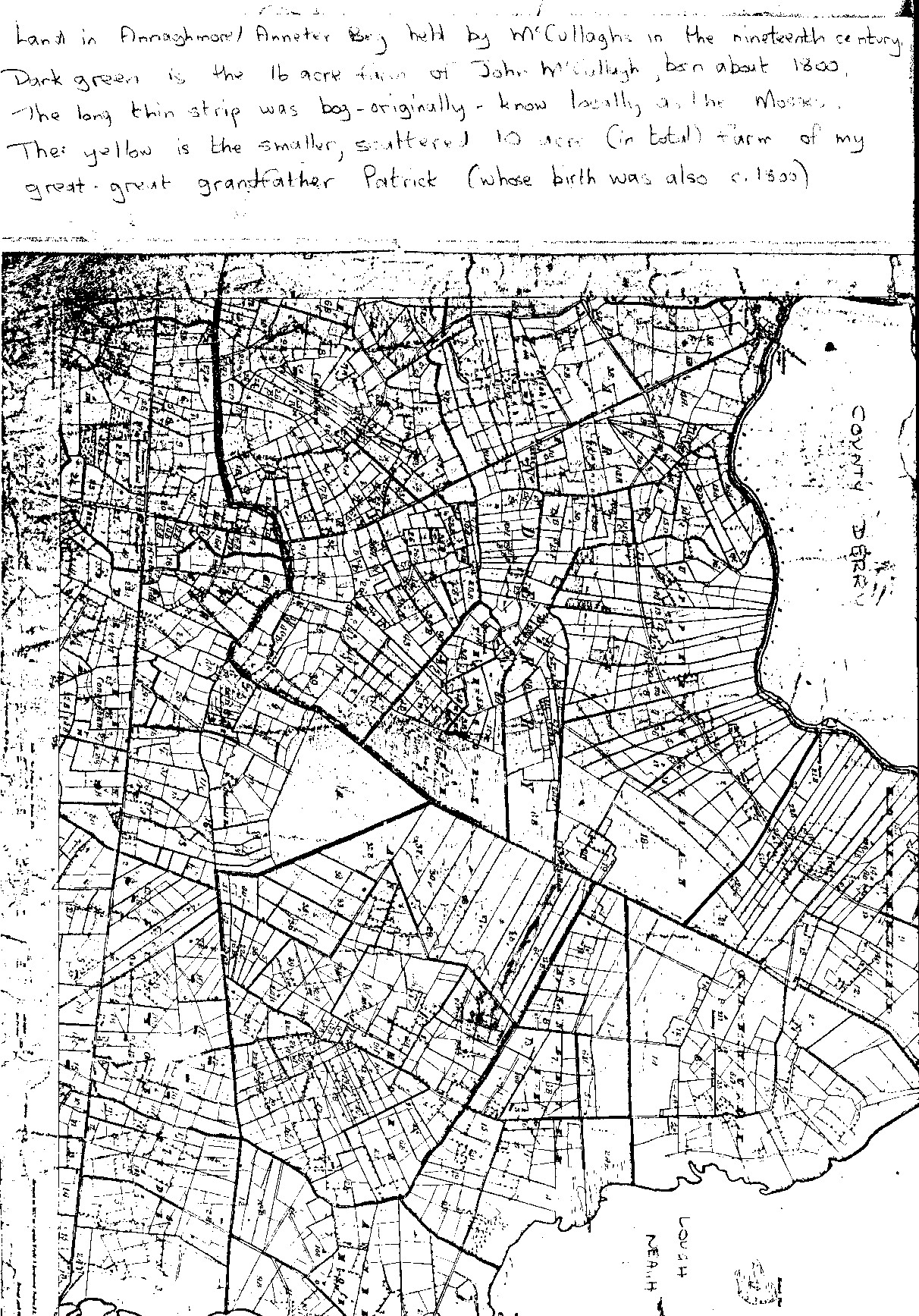

Still the poor were desperately poor. My great-great grandparents, for example, would scarcely have been able to scrape from their ten soggy acres enough potatoes to feed their family even in the very best of times. The Great Famine years one hundred and fifty years ago were the very worst of times. The blight that struck in consecutive years destroyed the greater part of, or in the worst years, the whole crop. My McCullagh ancestors suffered under it as much as most. Their land holdings were very small - (see maps and charts in Source Files). Some of them joined the floods of people taking the emigrant ships. They were usually the young and the most enterprising. Those who remained had little with which to build a future for themselves. It was an insecure and deprived future without even the comfort of the company of their siblings.

After the Famine people were unwilling to marry young lest they should go on to have a large family that they could not support. Sometimes only the dread of being left alone in old age persuaded the ageing bachelor or spinster to marry. I am convinced this was so for Francis and Alice, my McCullagh great grandparents. Land clearance and farm amalgamation for grazing - now more lucrative for the landowners - was the order of the day. The Irish peasant's love affair with the land was now over. The happier, carefree days of an earlier generation were gone forever. The present was filled with hardship and the future with anxiety and fear. No one wanted to rear a large family any more. Most people who remained in Ireland stayed single well into middle life. In our family - some ages at marriage were: Eliza 29: Michael and Francis 30+ : Thomas 52.

My great grandparents surely were not young when they married. Francis McCullagh was forty-six when in July 1876 he married a local lady Alice Small who was in her fortieth year. (According to the records unearthed by Des Dineen, the marriage was consecrated four years previously in July 1872. The groom was described as Frank McCullagh. The witnesses were Hugh Devlin and Alicke (sic) Morgan.)

I am certain that my great grandparents would have tried immediately for a child who might support them in their old age. They would have been delighted at the birth of their only child Patrick (or was he?) on 6.12.1877. (The reader will see just how close our line came to extinction!)

At the christening the sponsors were William Conway and Eliza Small. For the registration of this birth the record reads: 11.12.1877 at Annaghmore, Patrick to Francis McCullough (sic) farmer, and Alice Small. Informant was Theresa Coyle of Kinrush who was present at the birth. (Theresa signed her name: - most entries have an X instead as most people were illiterate).

Sarah Hagan remembers Eliza

Francis and Alice would have expected their son to inherit the small farm. These hopes and ambitions were not to be fulfilled. This boy as a teenager would come to see his parents as old and their farm as not worth inheriting. He left Ardboe in his early twenties. Already his parents were pensioners - except that there wasn't yet any old age pension.

Francis inherited his small ten-acre farm (for its location see the map photocopies included in the Source Files) from his father Patrick. This Patrick - born in the early years of the nineteenth century had - (I believe, as does Des Dineen) a brother John who had inherited the larger (sixteen English acre) more fertile and better-drained farm on his father's death. This father's first name is I believe Francis - one of the most commonly recurring first names in the male line of our family. He is likely to be the Francis McCullock of Annavore who held 10 acres in the Tithe Applotment Book of 1826. [Ignore the misspelling. Names were only recently translated from the original Irish.]

I have no birth dates for John or Patrick but the latter had the older family and so may have been older! There might have been more children. There are no complete records this early!

This first Francis - our earliest known ancestor, is patriarch of a huge and widely dispersed clan today in Ardboe, Newry and - I believe - America, Canada and Australia. He lived through the 1798 Rebellion, being a contemporary of Henry Joy McCracken and Theobald Wolfe Tone. He was an adult when the Act of Union was passed. He did not own the land he farmed because the penal laws, barring Catholics from owning land, holding public office or voting were in force. For another century until the disestablishment of the (Protestant) Church in Ireland, much of Ireland's land would be held by and leased from Protestant clergymen. The McCullagh lands in Annaghmore were leased from the Venerable Archdeacon Stuart. He would have shown no interest other than in the rents due to him.

My great grandfather Francis McCullagh was born in 1830. He was the second child born to Patrick McCullagh and Maria Isabella (Devlin). His father's farm was smaller than that of his next-door neighbour and brother John McCullagh. (Patrick may even have married into the land rather than inherited it: Des Dineen and his researchers think that the land held and recorded in the Tithe Applottment Act of 1824 by Francis McCullock is identical with the lands recorded in the 1864 Griffiths Valuation in the name of John McCullagh - the man we speculate to be Francis McCullagh's (i.e. my great grandfather's) brother. Some translation of Irish/ English acres is required to sustain this speculation. The matter remains unproven!)

McCullagh Land at Ardboe

Whether or not John was given the larger and more fertile sixteen-acre farm, in the mid century the two brothers raised their separate families on the adjoining farms. Their family homes were themselves adjoined so that the children of these two families - first cousins - would have mixed and associated almost as one large family.

What were the farmhouses like?

In the 1860's they were very similar and taxed at the same level. By the turn of the century just one of them had been improved, as can be seen from this entry in the 1901 Census......

Annaghmore is a 365-acre townland in Ardboe, District Electoral Division of Munterevlin (Irish for Devlin country) County Tyrone. In 1901 there were 38 households in this townland that included No 29 .. household of Francis McCullagh a 70-year-old farmer and his wife Alice aged 65. Neither could read. Both were Roman Catholic, born in Co Tyrone. The house comprised three rooms with two windows in front. It was graded third class, with one outbuilding situated on its own holding. Next-door and attached No 30, had two rooms, with three windows and it was graded second class. Here lived Francis McCullagh junior, a 49-year-old farmer with his wife Mary aged 46 and their children John 12, Francis 11, Thomas 9 and James 7. All were R.C. born in Co Tyrone and could read and write. [Some discrepancy of age naturally arises. It didn't matter so much then. Most people, especially the illiterate didn't know their age and cared nothing about it.] By the 1911 Census house numbers had been changed. Also both my great grandparents were deceased. Their home had reverted to Patrick Ryan. Next door (now No 18) the home of Francis McCullagh (farmer, aged 65) was second class consisting of three rooms with four windows in front and four outbuildings. He had been married to Mary (aged 66) for 25 years. they had four children, all of them alive. Those at home were Francis 21 and Thomas 19, both farmers.

The mid-nineteenth century was the most dreadful period of crop failure, hunger and distress in Ireland's history. Poorer areas were proportionately more dependent on the potato crop than others. The availability of fish from the Lough surely helped but the prospects for the future were not good. Each man, unlike their father, was rearing a large family. There was no chance of subdividing further to provide land for the next generation. After the famine, sub-division was no longer an option. Farm amalgamation instead was the order of the day. The natural carefree spirit of the Irish was replaced by anxiety over the future. Emigration to England and America had begun in the previous century and more recently to Australia. Constantly letters were arriving back describing the better life to be had in the New World - often containing remittances and offers to help aspirant emigrants. A trickle of Irish emigration became a flood in the later Famine years and the flood became a deluge in the decades after that. Even the son and heir often departed.

Des Dineen in Australia traced his roots back to the (Australian) immigrant Henry McCullagh who arrived in Bacchus Marsh, Victoria, Australia about the year 1858. He had originated from Annaghmore, Ardboe, Co Tyrone.

The oral tradition in Australia tells that Henry was a man of some education and distinction. He gained a degree in Political Science - it is said - probably from the recently established Queen's College in Belfast [later to be Queen's University Belfast - my own alma mater - where some of my children are now studying!]. Henry went on to teach for a while in this college before he emigrated. His brother James and his wife later (some ten years later) joined him in Bacchus Marsh, Victoria. By that time Henry was married there to a lady who had also emigrated from Ireland - Bridget Brennan from Kilkenny. (Phil [Mussen] McCullagh, my sister-in-law has forbears of that name from Kilkenny!). These brothers were among the original settlers of this Australian town. By the time of James' and his wife's arrivals, the settlement was flourishing. Des also details some of the descendents of the (John) McCullaghs who remained in Ardboe. Included in the notes he supplied to me are photographs of the original Henry (Des' great grandfather) and his brother James's wife (Again, see Resource Files).

Des commissioned a family history research (Ulster Historical Foundation) on this - our common ancestors - some eight years before I did. Had I known this in time, I could have saved myself a great deal of work. As it is however, our separate inquiries have produced records that correspond remarkably well. In some small things I am of use to him. He has been a mine of information to me especially in regard to surviving members of the widely dispersed clan in Australia, USA and Canada. I hope to get from him addresses in America and Canada and perhaps one day expand the narrative to tell the tale of McCullaghs abroad. Perhaps Des will follow my example and narrate the history of McCullaghs in Australia.

For now I will continue with the fruits of my own research.

To summarise the emigrant McCullaghs of these families. There were five (in my opinion) John, Henry, James, Eleanor and Joseph. Certainly children in some parts of Ireland did die in those times without a record being made of their passing. The Ardboe church records suggest that didn’t happen here. Even the very poor had access to some food by the loughside. The local death rate rose only slightly (by some 4-8% I am led to believe) throughout the famine years. The least likely of a family to perish (except from disease) are the eldest, as these were.

The only children of these families who still remain unaccounted for (i.e. no emigration record nor further record of marriage or death in Ireland) are Eleanor (b. 6.7.1828) and Joseph (b. 4.4.1836) siblings of my great grandfather Francis. I hope Des Dineen will be able to check Australian immigration records of the 1850’s-1860’s for me to see if they went there after (or before!) Henry and James, their first cousins. This is the most obvious remaining loose end in my story.

I have checked USA emigration records in search of the passage of any children of these two families. It is difficult to check all the records of all emigrant ships but I have found what I believe to be the record of the passage of John McCullagh’s son John in 1859. Before his twenty-first birthday he set out alone for Derry, there to board the emigrant ship Zered, bound for Philadelphia. She sailed on 12 May 1859.

Why do I think this is him?

No home address is recorded on the ship’s log (nor on arrival) of any passenger. Logic is required to resolve the mystery. Our John left the family farm that would be his (there is no further record of him in Ireland). He did not follow his brothers to Australia. He was twenty years old and poor (the passenger had just one piece of luggage). His nearest port of embarkation was Derry. There cannot have been many John McCullaghs (correct spelling) of that age, of that hinterland emigrating at that time. On the passenger list John is described as a labourer. Had he stayed at home he would have inherited the lease of the sixteen-acre farm in Annaghmore. He had greater ambitions.

Now we know courtesy of Des Dineen that his brothers Henry and James (b.12.12.1841) emigrated to Australia. It was the later Francis (the second son of that name: the first had died in infancy) who inherited the farm.